Linking number

In mathematics, the linking number is a numerical invariant that describes the linking of two closed curves in three-dimensional space. Intuitively, the linking number represents the number of times that each curve winds around the other. The linking number is always an integer, but may be positive or negative depending on the orientation of the two curves.

The linking number was introduced by Gauss in the form of the linking integral. It is an important object of study in knot theory, algebraic topology, and differential geometry, and has numerous applications in mathematics and science, including quantum mechanics, electromagnetism, and the study of DNA supercoiling.

Contents |

Definition

Any two closed curves in space can be moved into exactly one of the following standard positions. This determines the linking number:

|

|||||

| linking number -2 | linking number -1 | linking number 0 | |||

|

|||||

| linking number 1 | linking number 2 | linking number 3 |

Each curve may pass through itself during this motion, but the two curves must remain separated throughout. This is formalized as regular homotopy, which further requires that each curve be an immersion, not just any map. However, this added condition does not change the definition of linking number (it does not matter if the curves are required to always be immersions or not), which is an example of an h-principle (homotopy-principle), meaning that geometry reduces to topology.

Proof

This fact (that the linking number is the only invariant) is most easily proven by placing one circle in standard position, and then show that linking number is the only invariant of the other circle. In detail:

- A single curve is regular homotopic to a standard circle (any knot can be unknotted if the curve is allowed to pass through itself). The fact that it is homotopic is clear, since 3-space is contractible and thus all maps into it are homotopic, though the fact that this can be done through immersions requires some geometric argument.

- The complement of a standard circle is homeomorphic to a solid torus with a point removed (this can be seen by interpreting 3-space as the 3-sphere with the point at infinity removed, and the 3-torus as two solid tori glued along the boundary), or the complement can be analyzed directly.

- The fundamental group of 3-space minus a circle is the integers, corresponding to linking number. This can be seen via the Seifert–Van Kampen theorem (either adding the point at infinity to get a solid torus, or adding the circle to get 3-space, allows one to computer the fundamental group of the desired space).

- Thus homotopy classes of a curve in 3-space minus a circle are determined by linking number.

- It is also true that regular homotopy classes are determined by linking number, which requires additional geometric argument.

Computing the linking number

There is an algorithm to compute the linking number of two curves from a link diagram. Label each crossing as positive or negative, according to the following rule[1]:

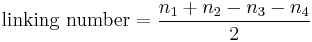

The total number of positive crossings minus the total number of negative crossings is equal to twice the linking number. That is:

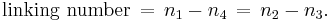

where n1, n2, n3, n4 represent the number of crossings of each of the four types. The two sums  and

and  are always equal,[2] which leads to the following alternative formula

are always equal,[2] which leads to the following alternative formula

Note that  involves only the undercrossings of the blue curve by the red, while

involves only the undercrossings of the blue curve by the red, while  involves only the overcrossings.

involves only the overcrossings.

Properties and examples

- Any two unlinked curves have linking number zero. However, two curves with linking number zero may still be linked (e.g. the Whitehead link).

- Reversing the orientation of either of the curves negates the linking number, while reversing the orientation of both curves leaves it unchanged.

- The linking number is chiral: taking the mirror image of link negates the linking number. Our convention for positive linking number is based on a right-hand rule.

- The winding number of an oriented curve in the x-y plane is equal to its linking number with the z-axis (thinking of the z-axis as a closed curve in the 3-sphere).

- More generally, if either of the curves is simple, then the first homology group of its complement is isomorphic to Z. In this case, the linking number is determined by the homology class of the other curve.

- In physics, the linking number is an example of a topological quantum number. It is related to quantum entanglement.

Gauss's integral definition

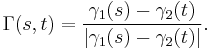

Given two non-intersecting differentiable curves  , define the Gauss map

, define the Gauss map  from the torus to the sphere by

from the torus to the sphere by

Pick a point in the unit sphere, v, so that orthogonal projection of the link to the plane perpendicular to v gives a link diagram. Observe that a point (s,t) that goes to v under the Gauss map corresponds to a crossing in the link diagram where  is over

is over  . Also, a neighborhood of (s,t) is mapped under the Gauss map to a neighborhood of v preserving or reversing orientation depending on the sign of the crossing. Thus in order to compute the linking number of the diagram corresponding to v it suffices to count the signed number of times the Gauss map covers v. Since v is a regular value, this is precisely the degree of the Gauss map (i.e. the signed number of times that the image of Γ covers the sphere). Isotopy invariance of the linking number is automatically obtained as the degree is invariant under homotopic maps. Any other regular value would give the same number, so the linking number doesn't depend on any particular link diagram.

. Also, a neighborhood of (s,t) is mapped under the Gauss map to a neighborhood of v preserving or reversing orientation depending on the sign of the crossing. Thus in order to compute the linking number of the diagram corresponding to v it suffices to count the signed number of times the Gauss map covers v. Since v is a regular value, this is precisely the degree of the Gauss map (i.e. the signed number of times that the image of Γ covers the sphere). Isotopy invariance of the linking number is automatically obtained as the degree is invariant under homotopic maps. Any other regular value would give the same number, so the linking number doesn't depend on any particular link diagram.

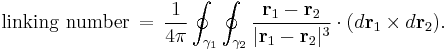

This formulation of the linking number of γ1 and γ2 enables an explicit formula as a double line integral, the Gauss linking integral:

This integral computes the total signed area of the image of the Gauss map (the integrand being the Jacobian of Γ) and then divides by the area of the sphere (which is 4π).

Generalizations

- Just as closed curves can be linked in three dimensions, any two closed manifolds of dimensions m and n may be linked in a Euclidean space of dimension

. Any such link has an associated Gauss map, whose degree is a generalization of the linking number.

. Any such link has an associated Gauss map, whose degree is a generalization of the linking number. - Any framed knot has a self-linking number obtained by computing the linking number of the knot C with a new curve obtained by slightly moving the points of C along the framing vectors. The self-linking number obtained by moving vertically (along the blackboard framing) is known as Kauffman's self-linking number.

- The linking number is defined for two linked circles; given three or more circles, one can define the Milnor invariants, which are a numerical invariant generalizing linking number.

- In algebraic topology, the cup product is a far-reaching algebraic generalization of the linking number, with the Massey products being the algebraic analogs for the Milnor invariants.

- A linkless embedding of an undirected graph is an embedding into three-dimensional space such that every two cycles have zero linking number. The graphs that have a linkless embedding have a forbidden minor characterization as the graphs with no Petersen family minor.

See also

- winding number

- differential geometry of curves

- link (knot theory)

- Hopf invariant

- kissing number

- writhe

Notes

- ^ This is the same labeling used to compute the writhe of a knot, though in this case we only label crossings that involve both curves of the link.

- ^ This follows from the Jordan curve theorem if either curve is simple. For example, if the blue curve is simple, then n1 + n3 and n2 + n4 represent the number of times that the red curve crosses in and out of the region bounded by the blue curve.

References

- - (2001), "Writhing number", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=W/w098170